Nebular hypothesis

| Star formation |

|---|

|

| Interstellar medium Molecular cloud Bok globule Dark nebula Young stellar object Protostar T Tauri star Herbig Ae/Be stars Nebular hypothesis |

| Object classes |

| Herbig–Haro object |

| Theoretical concepts |

| Initial mass function Jeans instability Kelvin-Helmholtz mechanism |

|

|

In cosmogony, the nebular hypothesis is the most widely accepted model explaining the formation and evolution of the Solar System. It was first proposed in 1734 by Emanuel Swedenborg.[1] Originally applied only to our own Solar System, this method of planetary system formation is now thought to be at work throughout the universe.[2] The widely accepted modern variant of the nebular hypothesis is Solar Nebular Disk Model (SNDM) or simply Solar Nebular Model.[3]

According to SNDM stars form in massive and dense clouds of molecular hydrogen—giant molecular clouds (GMC). They are gravitationally unstable, and matter coalesces to smaller denser clumps within, which then proceed to collapse and form stars. Star formation is a complex process, which always produces a gaseous protoplanetary disk around the young star. This may give birth to planets in certain circumstances, which are not well known. Thus the formation of planetary systems is thought to be a natural result of star formation. A sun-like star usually takes around 100 million years to form.[2]

The protoplanetary disk is an accretion disk which continues to feed the central star. Initially very hot, the disk later cools in what is known as the T tauri star stage; here, formation of small dust grains made of rocks and ices is possible. The grains may eventually coagulate into kilometer sized planetesimals. If the disk is massive enough the runaway accretions begin, resulting in the rapid—100,000 to 300,000 years—formation of Moon- to Mars-sized planetary embryos. Near the star, the planetary embryos go through a stage of violent mergers, producing a few terrestrial planets. The last stage takes around 100 million to a billion years.[2]

The formation of giant planets is a more complicated process. It is thought to occur beyond the so called snow line, where planetary embryos are mainly made of various ices. As a result they are several times more massive than in the inner part of the protoplanetary disk. What follows after the embryo formation is not completely clear. However, some embryos appear to continue to grow and eventually reach 5–10 Earth masses—the threshold value, which is necessary to begin accretion of the hydrogen–helium gas from the disk. The accumulation of gas by the core is initially a slow process, which continues for several million years, but after the forming protoplanet reaches about 30 Earth masses it accelerates and proceeds in a runaway manner. The Jupiter and Saturn–like planets are thought to accumulate the bulk of their mass during only 10,000 years. The accretion stops when the gas is exhausted. The formed planets can migrate over long distances during or after their formation. The ice giants like Uranus and Neptune are thought to be failed cores, which formed too late when the disk had almost disappeared.[2]

Contents |

History

The nebular hypothesis was first proposed in 1734 by Emanuel Swedenborg.[1] Immanuel Kant, who was familiar with Swedenborg's work, developed the theory further in 1755.[3] He argued that gaseous clouds—nebulae, which slowly rotate, gradually collapse and flatten due to gravity and eventually form stars and planets. A similar model was proposed in 1796 by Pierre-Simon Laplace.[3] It featured a contracting and cooling protosolar cloud—the protosolar nebula. As the nebula contracted, it flattened and shed rings of material, which later collapsed into the planets.[3] While the Laplacian nebular model dominated in the 19th century, it encountered a number of difficulties. The main problem was angular momentum distribution between the Sun and planets. The planets have 99% of the angular momentum, and this fact could not be explained by the nebular model.[3] As a result this theory of planet formation was largely abandoned at the beginning of the 20th century.

The fall of the Laplacian model stimulated scientists to find a replacement for it. During the 20th century many theories were proposed including the plantesimal theory of Thomas Chamberlin and Forest Moulton (1901), tidal model of Jeans (1917), accretion model of Otto Schmidt (1944), protoplanet theory of William McCrea (1960) and finally capture theory of Michael Woolfson.[3] In 1978 Andrew Prentice resurrected the initial Laplacian ideas about planet formation and developed the modern Laplacian theory.[3] None of these attempts were completely successful and many of the proposed theories were descriptive.

The birth of the modern widely accepted theory of planetary formation—Solar Nebular Disk Model (SNDM)—can be traced to the works of Soviet astronomer Victor Safronov.[4] His book Evolution of the protoplanetary cloud and formation of the Earth and the planets,[5] which was translated to English in 1972, had a long lasting effect on the way scientists think about the formation of the planets.[6] In this book almost all major problems of the planetary formation process were formulated and some of them solved. The Safronov's ideas were further developed in the works of George Wetherill, who discovered runaway accretion.[3] While originally applied only to our own Solar System, the SNDM was subsequently thought by theorists to be at work throughout the universe; over 430 extrasolar planets have since been discovered in our galaxy.

Solar Nebular Model: achievements and problems

Achievements

The star formation process naturally results in the appearance of accretion disks around young stellar objects.[7] At the age of about 1 million years, 100% of stars may have such disks.[8] This conclusion is supported by the discovery of the gaseous and dusty disks around protostars and T Tauri stars as well as by theoretical considerations.[9] The observations of the disks show that the dust grains inside them grow in size on the short time scale (over thousands of years) producing 1 centimeter sized particles.[10]

The accretion process, by which 1 km planetesimals grow into 1,000 km sized bodies, is well understood now.[11] This process develops inside any disk, where the number density of planetesimals is sufficiently high, and proceeds in a runaway manner. Growth later slows and continues as the oligarchic accretion. The end result is formation of planetary embryos of varying sizes, which depend on the distance from the star.[11] Various simulations have demonstrated that the merger of embryos in the inner part of the protoplanetary disk leads to the formation of a few Earth sized bodies. Thus the origin of terrestrial planets is now considered to be an almost solved problem.[12]

Problems

The physics of accretion disks encounters some problems.[13] The most important one is how the material, which is accreted by the protostar, loses its angular momentum. The momentum is probably transported to the outer parts of the disk, but the precise mechanism of this transport is not well understood. The process or processes responsible for the disappearance of the disks are also poorly known.[14][15]

The formation of planetesimals is the biggest unsolved problem in the Nebular Disk Model. How 1 cm sized particles coalesce into 1 km planetesimals is a mystery. This mechanism appears to be the key to the question as to why some stars have planets, while others have nothing around them, even dust belts.[16]

The formation of giant planets is another unsolved problem. Current theories are unable to explain how their cores can form fast enough to accumulate significant amounts of gas from the quickly disappearing protoplanetary disk.[11][17] The mean lifetime of the disks, which are less than 107 years, appears to be shorter than the time necessary for the core formation.[8]

Another problem of giant planet formation is their migration. Some calculations show that interaction with the disk can cause rapid inward migration, which, if not stopped, results in the planet reaching the "central regions still as a sub-Jovian object."[18]

Formation of stars and protoplanetary disks

Protostars

Stars are thought to form inside giant clouds of cold molecular hydrogen—giant molecular clouds roughly 300,000 times the mass of the Sun and 20 parsecs in diameter.[2][19] Over millions of years giant molecular clouds are prone to collapse and fragmentation.[20] These fragments then form small, dense cores which in turn collapse into stars.[19] The cores range in mass from a fraction to several times that of the Sun and are called protostellar (protosolar) nebulae.[2] They possess diameters of 0.01–0.1 pc (2,000–20,000 AU) and a particle number density of roughly 10,000 to 100,000 cm−3.[a][19][21]

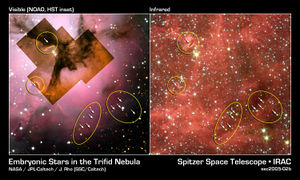

The initial collapse of a solar-mass protostellar nebula takes around 100,000 years.[2][19] Every nebula begins with a certain amount of angular momentum. Gas in the central part of the nebula, whose angular momentum is relatively low, undergoes fast compression and forms a hot hydrostatic (not contracting) core containing a small fraction of the mass of the original nebula.[22] This core forms the seed of what will become a star.[2][22] As the collapse continues, conservation of angular momentum means that the rotation of the infalling envelop accelerates,[15][23] which largely prevents the gas from directly accreting onto the central core. The gas is instead forced to spread outwards near its equatorial plane, forming a disk, which in turn accretes onto the core.[2][15][23] The core gradually grows in mass until it becomes a young hot protostar.[22] At this stage, the protostar and its disk are heavily obscured by the infalling envelope and are not directly observable.[7] In fact the remaining envelope's opacity is so high that even millimeter-wave radiation has trouble escaping from inside it.[2][7] Such objects are observed as very bright condensations, which emit mainly millimeter-wave and submillimeter-wave radiation.[21] They are classified as spectral Class 0 protostars.[7] The collapse is often accompanied by bipolar outflows—jets, which emanate along the rotational axis of the inferred disk. The jets are frequently observed in star-forming regions (see Herbig-Haro (HH) objects).[24] The luminosity of the Class 0 protostars is high — a protostar of the solar mass may radiate at up to 100 solar luminosities.[7] Their main source of energy is gravitational collapse; at this stage the protostars do not fuse hydrogen.[22][25]

As the envelope's material continues to infall onto the disk, it eventually becomes thin and transparent and the young stellar object (YSO) becomes observable; initially in far-infrared light and later in the visible.[21] Around this time the protostar begins to fuse deuterium and then ordinary hydrogen.[25] This birth of a new star occurs approximately 100,000 years after the collapse begins.[2] The external appearance of the YSO at this stage corresponds to the spectral class I protostars,[7] which are also called young T Tauri stars or evolved protostars.[7] By this time the forming star has already accreted much of its mass: the total mass of the disk and remaining envelope does not exceed 10–20% of the mass of the central YSO.[21]

At the next stage the envelope completely disappears, having been gathered up by the disk, and the protostar becomes a classical T Tauri star.[b] This happens after about 1 million years.[2] The mass of the disk around a classical T Tauri star is about 1–3% of the stellar mass, and it is accreted at the rate of between a 10 millionth to 1 billionth a solar mass per year.[26] A pair of bipolar jets is usually present as well.[27] The accretion explains all peculiar properties of classical T Tauri stars: strong flux in the emission lines (up to 100% of the intrinsic luminosity of the star), magnetic activity, photometric variability and jets.[28] The emission lines actually form as the accreted gas hits the "surface" of the star, which happens around its magnetic poles.[28] The jets are byproducts of accretion: they carry away excessive angular momentum. The classical T Tauri stage lasts about 10 million years.[2] The disk eventually disappears due to accretion onto central star, planet formation, ejection by jets and photoevaporation by UV-radiation from the central star and nearby stars.[29] As a result the young star becomes a weakly lined T Tauri star, which slowly, over hundreds of millions of years, evolves into an ordinary sun-like star.[22]

Protoplanetary disks

Under certain circumstances the disk, which can now be called protoplanetary, may give birth to a planetary system.[2] Protoplanetary disks have been observed around a very high fraction of stars in young star clusters. [8][30] They exist from the beginning of a star's formation, but at the earliest stages are unobservable due to the opacity of the surrounding envelope.[7] The disk of a Class 0 protostar is thought to be massive and hot. It is an accretion disk, which feeds the central protostar.[15][23] The temperature can easily exceed 400 K inside 5 AU and 1,000 K inside 1 AU.[31] The heating of the disk is primarily caused by the viscous dissipation of turbulence in it and by the infall of the gas from the nebula.[15][23] The high temperature in the inner disk causes most of the volatile material—water, organics, and some rocks to evaporate, leaving only the most refractory elements like iron. The ice can survive only in the outer part of the disk.[31]

The main problem in the physics of accretion disks is the generation of turbulence and the mechanism responsible for the high effective viscosity.[2] The turbulent viscosity is thought to be responsible for the transport of the mass to the central protostar and momentum to the periphery of the disk. This is vital for accretion, because the gas can be accreted by the central protostar only if it losses most of its angular momentum, which must be carried away by the small part of the gas drifting outwards.[14][15] The result of this process is the growth of both the protostar and of the disk radius, which can reach 1,000 AU if the initial angular momentum of the nebula is large enough.[23] Large disks are routinely observed in many star-forming regions such as the Orion nebula.[9]

The lifespan of the accretion disks is about 10 million years.[8] By the time the star reaches the classical T-Tauri stage, the disk becomes thinner and cools.[26] Less volatile materials start to condense close to its center, forming 0.1–1 μm dust grains that contain crystalline silicates.[10] The transport of the material from the outer disk can mix these newly formed dust grains with primordial ones, which contain organic matter and other volatiles. This mixing can explain some peculiarities in the composition of solar system bodies such as the presence of interstellar grains in the primitive meteorites and refractory inclusions in comets.[31]

Dust particles tend to stick to each other in the dense disk environment, leading to the formation of larger particles up to several centimeters in size.[32] The signatures of the dust processing and coagulation are observed in the infrared spectra of the young disks.[10] Further aggregation can lead to the formation of planetesimals measuring 1 km across or larger, which are the building blocks of planets.[2][32] Planetesimal formation is another unsolved problem of disk physics, as simple sticking becomes ineffective as dust particles grow larger.[16] The favorite hypothesis is formation by the gravitational instability. Particles several centimeters in size or larger slowly settle near the middle plane of the disk, forming a very thin—less than 100 km—and dense layer. This layer is gravitationally unstable and may fragment into numerous clumps, which in turn collapse into planetesimals.[2][16]

Planetary formation can also be triggered by gravitational instability within the disk itself, which leads to its fragmentation into clumps. Some of them, if they are dense enough, will collapse,[14] which can lead to rapid formation of gas giant planets and even brown dwarfs on the timescale of 1,000 years.[33] However it is only possible in massive disks—more massive than 0.3 solar masses. In comparison typical disk masses are 0.01–0.03 solar masses. Because the massive disks are rare, this mechanism of the planet formation is thought to be infrequent.[2][13] On the other hand, this mechanism may play a major role in the formation of brown dwarfs.[34]

The ultimate dissipation of protoplanetary disks is triggered by a number of different mechanisms. The inner part of the disk is either accreted by the star or ejected by the bipolar jets,[26][27] whereas the outer part can evaporate under the star's powerful UV radiation during the T Tauri stage[35] or by nearby stars.[29] The gas in the central part can either be accreted or ejected by the growing planets, while the small dust particles are ejected by the radiation pressure of the central star. What is finally left is either a planetary system, a remnant disk of dust without planets, or nothing, if planetesimals failed to form.[2]

Because planetesimals are so numerous, and spread throughout the protoplanetary disk, some survive the formation of a planetary system. Asteroids are understood to be left-over planetesimals, gradually grinding each other down into smaller and smaller bits, while comets are typically planetesimals from the farther reaches of a planetary system. Meteorites are samples of planetesimals that reach a planetary surface, and provide a great deal of information about the formation of our Solar System. Primitive-type meteorites are chunks of shattered low-mass planetesimals, where no thermal differentiation took place, while processed-type meteorites are chunks from shattered massive planetesimals.[36]

Formation of planets

Rocky planets

According to SNDM rocky planets form in the inner part of the protoplanetary disk, within the snow line, where the temperature is high enough to prevent condensation of water ice and other substances into grains.[37] This results in coagulation of purely rocky grains and later in the formation of rocky planetesimals.[c][37] Such conditions are thought to exist in the inner 3–4 AU part of the disk of a sun-like star.[2]

After small planetesimals—about 1 km in diameter—have formed by one way or another, runaway accretion begins.[11] It is called runaway because the mass growth rate is proportional to R4~M4/3, where R and M are the radius and mass of the growing body, respectively.[38] It is obvious that the specific (divided by mass) growth accelerates as the mass increases. This leads to the preferential growth of larger bodies at the expense of smaller ones.[11] The runaway accretion lasts between 10,000 and 100,000 years and ends when the largest bodies exceed approximately 1,000 km in diameter.[11] Slowing of the accretion is caused by gravitational perturbations by large bodies on the remaining planetesimals.[11][38] In addition, the influence of larger bodies stops further growth of smaller bodies.[11]

The next stage is called oligarchic accretion.[11] It is characterized by the dominance of several hundred of the largest bodies—oligarchs, which continue to slowly accrete planetesimals.[11] No body other than the oligarchs can grow.[38] At this stage the rate of accretion is proportional to R2, which is derived from the geometrical cross-section of an oligarch.[38] The specific accretion rate is proportional to M−1/3; and it declines with the mass of the body. This allows smaller oligarchs to catch up to larger ones. The oligarchs are kept at the distance of about 10·Hr (Hr=(M/3Ms)1/3 is Hill radius and Ms is the mass of the central star) from each other by the influence of the remaining planetesimals.[11] Their orbital eccentricities and inclinations remain small. The oligarchs continue to accrete until planetesimals are exhausted in the disk around them.[11] Sometimes nearby oligarchs merge. The final mass of an oligarch depends on the distance from the star and surface density of planetesimals and is called the isolation mass.[38] For the rocky planets it is up to 0.1 of the Earth mass, or one Mars mass.[2] The final result of the oligarchic stage is the formation of about 100 Moon- to Mars-sized planetary embryos uniformly spaced at about 10·Hr.[12] They are thought to reside inside gaps in the disk and to be separated by rings of remaining planetesimals. This stage is thought to last a few hundred thousand years.[2][11]

The last stage of rocky planet formation is the merger stage.[2] It begins when only a small number of planetesimals remains and embryos become massive enough to perturb each other, which causes their orbits to become chaotic.[12] During this stage embryos expel remaining planetesimals, and collide with each other. The result of this process, which lasts for 10 to 100 million years, is the formation of a limited number of Earth sized bodies. Simulations show that the number of surviving planets is on average from 2 to 5.[2][12][36][39] In the Solar System they may be represented by Earth and Venus.[12] Formation of both planets required merging of approximately 10–20 embryos, while an equal number of them were thrown out of the Solar System.[36] Some of the embryos, which originated in the asteroid belt, are thought to have brought water to Earth.[37] Mars and Mercury may be regarded as remaining embryos that survived that rivalry.[36] Rocky planets, which have managed to coalesce, settle eventually into more or less stable orbits, explaining why planetary systems are generally packed to the limit; or, in other words, why they always appear to be at the brink of instability.[12]

Giant planets

The formation of giant planets is an outstanding problem in the planetary sciences.[13] In the framework of the Solar Nebular Model two theories for their formation exist. The first one is the disk instability model, where giant planets form in the massive protoplanetary disks as a result of its gravitational fragmentation (see above).[33] The disk instability may also lead to the formation of brown dwarfs, which are usually classified as stars. The second possibility is the core accretion model, which is also known as the nucleated instability model.[13] The latter scenario is thought to be the most promising one, because it can explain the formation of the giant planets in relatively low mass disks (less than 0.1 solar masses). In this model giant planet formation is divided into two stages: a) accretion of a core of approximately 10 Earth masses and b) accretion of gas from the protoplanetary disk.[2][13]

Giant planet core formation is thought to proceed roughly along the lines of the terrestrial planet formation.[11] It starts with planetesimals, which then undergo the runaway growth followed by the slower oligarchic stage.[38] Hypotheses do not predict a merger stage, due to the low probability of collisions between planetary embryos in the outer part of planetary systems.[38] An additional difference is the composition of the planetesimals, which in the case of giant planets form beyond the so called snow line and consist mainly of ice—ice to rock ratio is about 4 to 1.[17] This enhances the mass of planetesimals fourfold. However the minimum mass nebular, which is capable of terrestrial planet formation, can only form 1–2 Earth mass cores at the distance of Jupiter (5 AU) within 10 million years.[38] The latter number represents the average lifetime of gaseous disks around sun-like stars.[8] The proposed solutions include enhanced mass of the disk—a tenfold increase would suffice;[38] protoplanet migration, which allows the embryo to accrete more planetesimals;[17] and finally accretion enhancement due to gas drag in the gaseous envelopes of the embryos.[17][40] Some combination of the above-mentioned ideas may explain the formation of the cores of gas giant planets such as Jupiter and perhaps even Saturn.[13] The formation of planets like Uranus and Neptune is more problematic, since no theory has been capable of providing for the in situ formation of their cores at the distance of 20–30 AU from the central star.[2] To resolve this issue an idea has been brought forward that they initially accreted in the Jupiter-Saturn region and then were scattered and migrated to their present location.[41]

Once the cores are of sufficient mass (5–10 Earth masses), they begin to gather gas from the surrounding disk.[2] Initially it is a slow process, which can increase the core masses up to 30 Earth masses in a few million years.[17][40] After that the accretion rates increase dramatically and the remaining 90% of the mass is accumulated in approximately 10,000 years.[40] The accretion of the gas stops when it is exhausted. This happens when a gap opens in the protoplanetary disk.[42] In this model ice giants—Uranus and Neptune—are failed cores that began gas accretion too late, when almost all gas had already disappeared. The post runaway gas accretion stage is characterized by migration of the newly formed giant planets and continued slow gas accretion.[42] Migration is caused by the interaction of the planet sitting in the gap with the remaining disk. It stops when the protoplanetary disk disappears or when the end of the disk is attained. The latter case corresponds to the so called hot Jupiters, which are likely to have stopped their migration when they reached the inner hole in the protoplanetary disk.[42]

Giant planets can significantly influence terrestrial planet formation. The presence of giants tends to increase eccentricities and inclinations of planetesimals and embryos in the terrestrial planet region (inside 4 AU in the Solar System).[36][39] On the one hand, if giant planets form too early they can slow or prevent inner planet accretion. On the other hand, if they form near the end of the oligarchic stage, as is thought to have happened in the Solar System, they will influence the merges of planetary embryos making them more violent.[36] As a result the number of terrestrial planets will decrease and they will be more massive.[43] In addition, the size of the system will shrink, because terrestrial planets will form closer to the central star. In the Solar System the influence of giant planets, particularly that of Jupiter, is thought to have been limited because they are relatively remote from the terrestrial planets.[43]

The region of a planetary system adjacent to the giant planets will be influenced in a different way.[39] In such a region eccentricities of embryos may become so large that they may pass close to a giant planet. As a result they may and probably will be thrown out of the planetary system.[d][36][39] If all embryos are removed then no planets will form in this region.[39] An additional consequence is that a huge number of small planetesimals will remain, because giant planets are incapable of clearing them all out without the help of embryos. The total mass of remaining planetesimals will be small, because cumulative action of the embryos before their ejection and giant planets is still strong enough to remove 99% of the small bodies.[36] Such a region will eventually evolve into an asteroid belt, which is a full analog of the main asteroid belt in the Solar System located at the distance 2 to 4 AU from the Sun.[36][39]

Meaning of accretion

Use of the term accretion disk for the protoplanetary disk leads to confusion over the planetary accretion process. The protoplanetary disk is sometimes referred to as an accretion disk, because while the young T Tauri-like protostar is still contracting, gaseous material may still be falling onto it, accreting on its surface from the disk's inner edge.[23]

However, that meaning should not be confused with the process of accretion forming the planets. In this context, accretion refers to the process of cooled, solidified grains of dust and ice orbiting the protostar in the protoplanetary disk, colliding and sticking together and gradually growing, up to and including the high energy collisions between sizable planetesimals.[11]

In addition, the giant planets probably had accretion disks of their own, in the first meaning of the word. The clouds of captured hydrogen and helium gas contracted, spun up, flattened, and deposited gas onto the surface of each giant protoplanet, while solid bodies within that disk accreted into the giant planet's regular moons.[44]

See also

- Formation and evolution of the Solar System

- History of Earth

- Asteroid Belt, Kuiper Belt, and Oort Cloud

- Bok globule, Herbig-Haro object

- T Tauri star

Notes

- ^ Compare it with the particle number density of the air at the sea level—2.8×1019 cm−3.

- ^ The T Tauri stars are young stars with mass less than about 2.5 solar masses showing a heightened level of activity. They are divided into two classes: weakly lined and classical T Tauri stars.[45] The latter have accretion disks and continue to accrete hot gas, which manifests itself by strong emission lines in their spectrum. The former do not possess accretion disks. Classical T Tauri stars evolve into weakly lined T Tauri stars.[46]

- ^ The planetesimals near the outer edge of the terrestrial planet region—2.5 to 4 AU from the Sun—may accumulate some amount of ice. However the rocks will still dominate, like in the outer main belt in the Solar System.[37]

- ^ As a variant they may collide with the central star or a giant planet.[39]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Swedenborg, Emanuel (1734). (Principia) Latin: Opera Philosophica et Mineralia (English: Philosophical and Mineralogical Works). I.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 Montmerle, Thierry; Augereau, Jean-Charles; Chaussidon, Marc et al. (2006). "Solar System Formation and Early Evolution: the First 100 Million Years". Earth, Moon, and Planets (Spinger) 98: 39–95. doi:10.1007/s11038-006-9087-5. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006EM%26P...98...39M.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Woolfson, M.M. (1993). "Solar System – its origin and evolution". Q. J. R. Astr. Soc. 34: 1–20. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1993QJRAS..34....1W. For details of Kant's position, see Stephen Palmquist, "Kant's Cosmogony Re-Evaluated", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 18:3 (September 1987), pp.255-269.

- ↑ Henbest, Nigel (1991). "Birth of the planets: The Earth and its fellow planets may be survivors from a time when planets ricocheted around the Sun like ball bearings on a pinball table". New Scientist. http://space.newscientist.com/channel/solar-system/comets-asteroids/mg13117837.100. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ↑ Safronov, Viktor Sergeevich (1972). Evolution of the Protoplanetary Cloud and Formation of the Earth and the Planets. Israel Program for Scientific Translations. ISBN 0706512251.

- ↑ Wetherill, George W. (1989). "Leonard Medal Citation for Victor Sergeevich Safronov". Meteoritics 24: 347. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1989Metic..24..347W.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Andre, Philippe; Montmerle, Thierry (1994). "From T Tauri stars protostars: circumstellar material and young stellar objects in the ρ Ophiuchi cloud". The Astrophysical Journal 420: 837–862. doi:10.1086/173608. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994ApJ...420..837A.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Haisch, Karl E.; Lada, Elizabeth A.; Lada, Charles J. (2001). "Disk frequencies and lifetimes in young clusters". The Astrophysical Journal 553: L153–L156. doi:10.1086/320685. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2001ApJ...553L.153H.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Padgett, Deborah L.; Brandner, Wolfgang; Stapelfeldt, Karl L. et al. (1999). "Hubble space telescope/nicmos imaging of disks and envelopes around very young stars". The Astronomical Journal 117: 1490–1504. doi:10.1086/300781. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999AJ....117.1490P.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kessler-Silacci, Jacqueline; Augereau, Jean-Charles; Dullemond, Cornelis P. et al. (2006). "c2d SPITZER IRS spectra of disks around T Tauri stars. I. Silicate emission and grain growth". The Astrophysical Journal 639: 275–291. doi:10.1086/300781. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999AJ....117.1490P.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 Kokubo, Eiichiro; Ida, Shigeru (2002). "Formation of protoplanet systems and diversity of planetary systems". The Astrophysical Journal 581: 666–680. doi:10.1086/344105. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002ApJ...581..666K.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Raymond, Sean N.; Quinn, Thomas; Lunine, Jonathan I. (2006). "High-resolution simulations of the final assembly of earth-like planets 1: terrestrial accretion and dynamics". Icarus 183: 265–282. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.03.011. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006Icar..183..265R.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Wurchterl, G. (2004). "Planet Formation Towards Estimating Galactic Habitability". In P. Ehrenfreund et al.. Astrobiology:Future Perspectives. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 67–96. http://www.springerlink.com/content/pr4rj4240383l585/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Klahr, H.H.; Bodenheimer, P. (2003). "Turbulence in accretion disks: vorticity generation and angular momentum transport via the global baroclinic instability". The Astrophysical Journal 582: 869–892. doi:10.1086/344743. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ApJ...582..869K.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Nakamoto, Taishi; Nakagawa, Yushitsugu (1994). "Formation, early evolution, and gravitational stability of protoplanetary disks". The Astrophysical Journal 421: 640–650. doi:10.1086/173678. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994ApJ...421..640N.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Youdin, Andrew N.; Shu, Frank N. (2002). "Planetesimal formation by gravitational instability". The Astrophysical Journal 580: 494–505. doi:10.1086/343109. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002ApJ...580..494Y.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Inaba, S.; Wetherill, G.W.; Ikoma, M. (2003). "Formation of gas giant planets: core accretion models with fragmentation and planetary envelope" (pdf). Icarus 166: 46–62. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.08.001. http://isotope.colorado.edu/~astr5835/Inaba%20et%20al%202003.pdf.

- ↑ Papaloizou 2007 page 10

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Pudritz, Ralph E. (2002). "Clustered Star Formation and the Origin of Stellar Masses". Science 295 (5552): 68–75. doi:10.1126/science.1068298. PMID 11778037. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/295/5552/68.

- ↑ Clark, Paul C.; Bonnell, Ian A. (2005). "The onset of collapse in turbulently supported molecular clouds". Mon.Not.R.Astron.Soc. 361: 2–16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09105.x. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005MNRAS.361....2C.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Motte, F.; Andre, P.; Neri, R. (1998). "The initial conditions of star formation in the ρ Ophiuchi main cloud: wide-field millimeter continuum mapping". Astron. Astrophys. 336: 150–172. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1998A%26A...336..150M.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Stahler, Steven W.; Shu, Frank H.; Taam, Ronald E. (1980). "The evolution of protostars: II The hydrostatic core". The Astrophysical Journal 242: 226–241. doi:10.1086/158459. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1980ApJ...242..226S.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Yorke, Harold W.; Bodenheimer, Peter (1999). "The formation of protostellar disks. III. The influence of gravitationally induced angular momentum transport on disk structure and appearance". The Astrophysical Journal 525: 330–342. doi:10.1086/307867. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999ApJ...525..330Y.

- ↑ Lee, Chin-Fei; Mundy, Lee G.; Reipurth, Bo et al. (2000). "CO outflows from young stars: confronting the jet and wind models". The Astrophysical Journal 542: 925–945. doi:10.1086/317056. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000ApJ...542..925L.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Stahler, Steven W. (1988). "Deuterium and the Stellar Birthline". The Astrophysical Journal 332: 804–825. doi:10.1086/166694. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1988ApJ...332..804S.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hartmann, Lee; Calvet, Nuria; Gullbring, Eric; D’Alessio, Paula (1998). "Accretion and the evolution of T Tauri disks". The Astrophysical Journal 495: 385–400. doi:10.1086/305277. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1998ApJ...495..385H.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Shu, Frank H.; Shang, Hsian; Glassgold, Alfred E.; Lee, Typhoon (1997). "X-rays and Fluctuating X-Winds from Protostars". Science 277: 1475–1479. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1475. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/277/5331/1475.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Muzerolle, James; Calvet, Nuria; Hartmann, Lee (2001). "Emission-line diagnostics of T Tauri magnetospheric accretion. II. Improved model tests and insights into accretion physics". The Astrophysical Journal 550: 944–961. doi:10.1086/319779. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2001ApJ...550..944M.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Adams, Fred C.; Hollenbach, David; Laughlin, Gregory; Gorti, Uma (2004). "Photoevaporation of circumstellar disks due to external far-ultraviolet radiation in stellar aggregates". The Astrophysical Journal 611: 360–379. doi:10.1086/421989. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2004ApJ...611..360A.

- ↑ Megeath, S.T.; Hartmann, L.; Luhmann, K.L.; Fazio, G.G. (2005). "Spitzer/IRAC photometry of the ρ Chameleontis association". The Astrophysical Journal 634: L113–L116. doi:10.1086/498503. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005ApJ...634L.113M.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Chick, Kenneth M.; Cassen, Patrick (1997). "Thermal processing of interstellar dust grains in the primitive solar environment". The Astrophysical Journal 477: 398–409. doi:10.1086/303700. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1997ApJ...477..398C.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Michikoshi, Shugo; Inutsuka, Shu-ichiro (2006). "A two-fluid analysis of the kelvin-helmholtz instability in the dusty layer of a protoplanetary disk: a possible path toward planetesimal formation through gravitational instability". The Astrophysical Journal 641: 1131–1147. doi:10.1086/499799. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006ApJ...641.1131M.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Boss, Alan P. (2003). "Rapid formation of outer giant planets by disk instability". The Astrophysical Journal 599: 577–581. doi:10.1086/379163. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ApJ...599..577B.

- ↑ Stamatellos, Dimitris; Hubber, David A.;Whitworth, Anthony P. (2007). "Brown dwarf formation by gravitational fragmentation of massive, extended protostellar discs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 382: L30–L34. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2007.00383.x. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/bib_query?arXiv:0708.2827.

- ↑ Font, Andreea S.; McCarthy, Ian G.; Johnstone, Doug; Ballantyne, David R. (2004). "Photoevaporation of circumstellar disks around young stars". The Astrophysical Journal 607: 890–903. doi:10.1086/383518. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2004ApJ...607..890F.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 36.7 36.8 Bottke, William F.; Durda, Daniel D.; Nesvorny, David et al. (2005). "Linking the collisional history of the main asteroid belt to its dynamical excitation and depletion" (pdf). Icarus 179: 63–94. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.05.017. http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~bottke/Reprints/Bottke_Icarus_2005_179_63-94_Linking_Collision_Dynamics_MB.pdf.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Raymond, Sean N.; Quinn, Thomas; Lunine, Jonathan I. (2007). "High-resolution simulations of the final assembly of Earth-like planets 2: water delivery and planetary habitability". Astrobiology 7 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.06-0126. PMID 17407404. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007AsBio...7...66R.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 38.8 Thommes, E.W.; Duncan, M.J.; Levison, H.F. (2003). "Oligarchic growth of giant planets". Icarus 161: 431–455. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(02)00043-X. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003Icar..161..431T.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 Petit, Jean-Marc; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2001). "The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt" (pdf). Icarus 153: 338–347. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6702. http://www.gps.caltech.edu/classes/ge133/reading/asteroids.pdf.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Fortier, A.; Benvenuto, A.G. (2007). "Oligarchic planetesimal accretion and giant planet formation". Astron.Astrophys. 473: 311–322. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066729. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007A%26A...473..311F.

- ↑ Thommes, Edward W.; Duncan, Martin J.; Levison, Harold F. (1999). "The formation of Uranus and Neptune in the Jupiter-Saturn region of the Solar System" (pdf). Nature 402 (6762): 635–638. doi:10.1038/45185. PMID 10604469. http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~hal/PDF/un-scat_nature.pdf.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Papaloizou, J.C.B.; Nelson, R.P.; Kley, W. et al. (2007). "Disk-Planet Interactions During Planet Formation". In Bo Reipurth; David Jewitt; Klaus Keil. Protostars and Planets V. Arizona Press. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007prpl.conf..655P.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Levison, Harold F.; Agnor, Craig (2003). "The role of giant planets in terrestrial planet formation" (pdf). The Astronomical Journal 125: 2692–2713. doi:10.1086/374625. http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~hal/PDF/tfakess.pdf.

- ↑ Canup, Robin M.; Ward, William R. (2002). "Formation of the Galilean Satellites: Conditions of Accretion" (pdf). The Astronomical Journal 124: 3404–3423. doi:10.1086/344684. http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~robin/cw02final.pdf.

- ↑ Mohanty, Subhanjoy; Jayawardhana, Ray; Basri, Gibor (2005). "The T Tauri Phase down to Nearly Planetary Masses: Echelle Spectra of 82 Very Low Mass Stars and Brown Dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal 626: 498–522. doi:10.1086/429794. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005ApJ...626..498M.

- ↑ Martin, E.L.; Rebolo, R.; Magazzu, A.; Pavlenko Ya.V. (1994). "Pre-main sequence lithium burning". Astron. Astrophys. 282: 503–517. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994A%26A...282..503M.